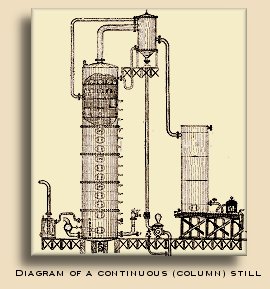

Now that you know all about rectification, a mid-to-late 19th century phenomenon, let's go a little earlier in the century. As Chris Middleton pointed out in his comment, there were multiple transitional technologies along the way to the continuous still as we know it today in bourbon-making. Although the earliest form of still, the alembic, is still in wide use these transitional designs mostly died out as the modern continuous still emerged.

A conversation here about one of the most important transitional forms started a year and a half ago with a post about how Leopold Brothers Distillery in Colorado was trying to recreate the distinctive Maryland ryes of legend. One characteristic of these early ryes, made in and around Baltimore and also Philadelphia, was the chamber still.

We heard from David Wondrich, Chris Middleton, Todd Leopold, Thomas McKenzie, and others on the subject. We learned that chamber stills were made of copper but also sometimes wood. There is an explanation of how such a still works here. We were all over it that June.

Now we return to Leopold Brothers and Todd Leopold, who has -- along with the folks at Louisville's Vendome Copper and Brass -- designed and built a production scale chamber still. It is copper, not wood, stands about 20 feet high, and has four chambers.

Innovation like this, by the way, is what it means to be a craft distiller.

As in a column still, steam is introduced at the bottom and mash enters at the top. Gravity is used to move the mash through the system, but unlike in a column, steam and mash can 'work' in each chamber as long as the distiller wants.

Because different alcohols and congeners boil at different temperatures, sending mash through three heat 'zones' effectively frees the alcohol, concentrates good congeners, and eliminates bad ones.

As each batch moves from chamber to chamber, another batch is on its heels. The process is continuous, but in a batch sort of way.

The chamber still is a particularly American solution because it allows distilling on the grain, which has always been practiced in America. In Scotland and Ireland, whiskey is distilled on a wash, from which all solids have been removed. This allows them to use large but relatively simple alembic stills.

Leopold became fixated on the chamber still because it figures so prominently in the early history of rye whiskey. It also solves a production dilemma for Leopold Brothers. They need more whiskey production than their pot and pot hybrid stills alone can deliver, but they don't want the huge output of a full-on column still. They already have one for making neutral spirits but for whiskey, "a column still is a volume instrument," says Leopold. "It doesn't make sense to buy one if you aren't going to run an awful lot of mash through it around the clock." A three-chamber still is a nice, happy medium.

"We have no interest in becoming a large distillery," he says. "That's not our path."

The difference between a continuous still and a chamber still is like the difference between an espresso machine and a French press coffee maker. In the former, steam is forced through the grounds in seconds. In the latter, grounds linger and steep in the hot water to taste. The results are both coffee, but very different.

For most continuous bourbon stills, mash is inside the still in contact with steam for about three minutes. In the three-chamber still it's more like an hour. Both technologies extract all of the alcohol from the mash, but the chamber still extracts more flavor.

It isn't just the unique still. At Leopold's request, a Colorado farmer has planted 100 acres of an heirloom rye strain that was used by distillers in Maryland and Pennsylvania, and also by bakers in the Carolinas. Its difference, compared to modern strains, is starch content. Modern cereals are bred for high starch content. Starch becomes alcohol, so more starch means more yield, but starch content increases at the expense of flavor.

Modern rye strains are about 70 percent starch but the one Leopold is using is about 64 percent. "It has a much richer, nutty and floral flavor," says Leopold.

You can see where this is going. Both the still and the grain variety are less efficient but produce a more flavorful spirit.

"We are trying to recreate the flavors of those original ryes simply because they are lost to time," says Leopold. "It would be a shame to let such a glorious tradition of American whiskey production that was all but wiped out by Prohibition stay wiped out."

From the still's thumper, the distillate goes into the barrel with no additional rectification. A lot of work has gone into this recreation but now comes the hardest part; waiting while it ages.